|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tatjana Grindenko The ceaseless search for the perfect sound

Before we start talking music, I'd be interested to know whether it is true that in the last few years you have been interested in cars and motor racing. Cars and violins do not seem to have much in common.It's simple: I love cars. Particularly four wheel-drives. I think that they are the best thing that the car industry has produced. The Porsche is a fantastic make of care. I only drove one once, I think it was a bit too much for me. Recently though I have bought a new 2000 CC rally model, which I am just finishing tuning. Isn 't it dangerous for a violinist to take part in car rallies? Cars are not only a sport for me. I am absolutely convinced that man can develop thanks either to any experience if he/she needs, or to the capacity to grow. Cars have given me a different scale of values. Let's talk about music. You founded the first orchestra in Eastern Europe to be dedicated to playing  baroque music with original instruments. What made you choose baroque music, you, who up until the 60's

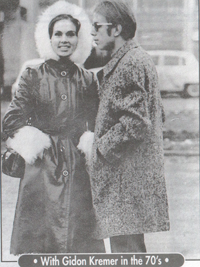

were considered with Gidon Kremer and Vladimir Spivakov, to be one of the greatest Romantic violinists?

baroque music with original instruments. What made you choose baroque music, you, who up until the 60's

were considered with Gidon Kremer and Vladimir Spivakov, to be one of the greatest Romantic violinists?I have always been interested in early music and when I started playing it I realised that everything I had been doing, and everything I had been searching for, was wrong. In the 60's I made a record of some music by Buxtehude; I am now ashamed of that record, but even then I was not satisfied with it. I was playing it in the same way as I would have played Tchaikovsky or Brahms... it was terrible. At the time I couldn't find any other way to play that repertory. I read the manuscripts by Geminiani and Corelli and his pupils; I found that they had a visual value, but I couldn't understand what was behind it all. Then Vladimir Martynov said to me: "You will never know how to play music from that period until you understand the why's and wherefore's of Limbourgs' art, the structure and principles of their miniatures". Only then did I discover the tables dedicated to the Limbourgs' seasons, and I was deeply impressed. We are talking about the years from '75 to '76. I started by playing renaissance music and then something was getting through to me. Above all when we played and sang troubadour songs, that kind of early repertory. In another culture completely I began to understand that the spirituality that we put into early music very often has no relation to it. I have no idea what my life would have been if I had not heard the St. Matthew Passion directed by Harnoncourt. Marvellous, absolutely marvellous! It was a shock for me, I didn't play the violin for two years after that! It was clear to me that what I had been taught was a lie and a swindle. My "real life" started with Harnoncourt. What were the most difficult things that you had to face at that time? It was very hard to find musicians; I wanted to enlarge my group, but couldn't. Musicians learn to perform according to classical methods, based on romantic music, so it is difficult to change their way of seeing things. Not only did the performers psychology have to be changed but also the way they used their lands on their instruments and their technique; I don't know which is more complicated, because the psychology of a normal performer is based on self-expression: in other words, the musician chooses the music he wants to play so that he can express his own ideas. My way of thinking is completely opposite to that of musicians in the old days who did not have to express themselves in the same way, because they were playing their own music. If we performers, and I say this as a Romantic violinist, talk constantly from the stage, then early music is the very thing we should now being trying to talk about. Performers in the 16th and 17th century were both composers and musicians, so there weren't the same problems as there are today in performing, that is playing what is written for the public. I feel sure that the difficulty in psychology is the most complex thing. Our lives have become so vulgar and coarse, there is no distinction between West and East, socialism and capitalism, our lives are vulgar and coarse as far as expressing our sentiments is concerned. You can see this everywhere, even in the way we play, it is a characteristic of the 20th century. Why? A very important thing in the musical world strange through it may seem, is social. For example it is very difficult to imagine the President or the members of the president government being very knowledgeable in art or music. History tells us though, the Kings and Emperors could also be excellent musicians. Nowadays such finesse in taste doesn't exist any more. How do you organize the work you did with the baroque group? Some people have to practice, others, and I think that I am one of them, only need to listen and understand the basics: what and why. The first thing 1 did was to study singing: I listened to records by Delerd, so what I did when playing the violin was a result of studying the art of singing. Then everyone realised that something had happened to me, they knew me and loved my romantic violin playing, the public believed in me. It is extremely important for a musician who wants to bring in something new, to be well known. They loved me whatever I did, and thought that my way was the right one. I was afraid of adding other musicians to the orchestra: we hadn't got any money, but we found some enthusiasts who wanted to take part at all costs. In our first few concerts we soon got over our difficulties. It almost makes me laugh to think that Jury Bashmet was interested in this kind of music when we started. He played in my first baroque orchestra as did the cellos of the State Symphony Orchestra, such as Michail Milman. Everyone has played in my ensemble, even the first violin of the Slivakova Orchestra. They came, they played and they left. Why? Not everyone is prepared to change their way of life. It means hard work, you realise that you have got to work hard. You have to give up almost everything, a thing that I did. My career as a romantic violinist had finished. A new life was starting for me. I always try to live according to what I believe in: if I have to do something I don't believe in, I give it up, even if I have been made very interesting offers. We know from your biography that you had ten years in which planning concerts and performing was difficult. They have only stopped me from performing twice in my life: the first was when I wanted to go to a competition in Brussels. I wasn't allowed to leave the country because an anonymous letter was found about me. I know neither who sent it nor what its contents were. A few years later I was allowed to take part in the competition in  Wieniavsky in Poland, where I won the first prize; this allowed me to travel around both with Gidon Kremer and

on my own for two or three years. Later on I went on tour America with the State Symphony Orchestra. Maxim

Shostakovich was the conductor and during the tour he asked for political asylum. In the Soviet Union at that

time the law said that if someone who was with you decided to stay abroad, you would be taken hostage. That time

I was the hostage.

Wieniavsky in Poland, where I won the first prize; this allowed me to travel around both with Gidon Kremer and

on my own for two or three years. Later on I went on tour America with the State Symphony Orchestra. Maxim

Shostakovich was the conductor and during the tour he asked for political asylum. In the Soviet Union at that

time the law said that if someone who was with you decided to stay abroad, you would be taken hostage. That time

I was the hostage.

How did it actually happen? I was playing Mozart's Fifth Symphony in the first part of the program. Usually I didn't listen to the second part, and I used to wait in the bus until the end of the concert. I had fallen asleep. The Orchestra's official bodyguard woke me up (orchestras, athletes and dance companies were always accompanied by KGB agents when they went on to So they stopped you giving any concerts for ten years? In those 9-10 years I could have gone to Krennikov, played with him and been free, but I couldn't bring myself to do it. My friends were Schnittke, Silvestrov, Gubaidulina and Part. Friends are so important. I thought that if I had gone to Krennikov they wouldn't have spoken to me again.. At that time they never compromised, they were essentially honest people. Krennikov and those with him were the official part, the party, all those who were outside the circle were the dissident part: official music and dissident music. Two different worlds: Krennikov, and I would have travelled the world over, or Schnittke and Gubaidulina ur), I was arrested and twelve hours later I was back in Moscow. Only then did I know what Maxim had decided to do - and my manuscripts and other personal effects were in my case in his car. It took six months to get it them back. And I was very lucky to get them back at all!. I made my choice. Did you choose not to play any more? No, I was made to stop playing. For years I wasn't even allowed to play in the socialist countries, and for some time I could neither play in concerts in Moscow and Leningrad nor record for the radio. Our system allowed each artiste to do a number of concerts each year in the main concert halls in Moscow and the whole of the Soviet Union, on the basis of the prizes they had won and the importance of the concerts they had given. Then suddenly I wasn't allowed to give concerts any more either in the Great Hall of the Conservatory or in the Tchaikovsky Hall. They only offered me concerts in psychiatric hospitals, prisons and out in the wastes of Siberia. But we often organized unofficial concerts, which attracted the audiences. And the audience was not made up of the same people who went to the Great Hall; they were the avant-garde, the most clever physicists, the best mathematicians, the cream of Moscow's intelligenija and culture. In Riga, when Gidon and I played in concerts the hall wasn't full, but when we gave a series of avant-garde music concerts, the theatre was so full that there were people waiting outside. Riga's intelligenija, scientists, doctors came... these were the 74's and 75's. At that time you were a great contemporary music enthusiast. I loved playing Stockhausen, Cage, Silvestrov and Martynov... When we played Cage's music it always created a scandal. We started the concerts with "Autobiography for 4 tape recorders and voice", after this the audience was in shock and we could play what ever we wanted. The audience was ready to enjoy it. We did a lot of happenings and these were the very first ones to take place in Russia. When we did happenings we often completely improvised - and not only musically, and we invited the audience to take part. Once in Riga the evening finished in a catastrophe. The audience were so enthusiastic that they completely destroyed all our equipment. The group was made up of Liubimov, Sereza Sovelev, Martynov, Artimiov (the first Russian to compose electronic music and who wrote the music for Tarkovskij's films; he now lives in Hollywood). There were 5-6 musicians in the group. From romantic to baroque music. I've heard that you like rock music and jazz and are particularly interested in contemporary music: some of the most important works such as the Concerto Grosso N 1 by Schnittke, Tabula Rasa by Arvo Part, "Hay que caminar", the last piece of music written by Luigi Nona were dedicated to you and Gidon Kremer, and Martynov, Silvestrov and Backy dedicated music to you. When I abandoned playing Romantic music I continued playing baroque music. I played  in the "Boomerang" rock group

in 1974. Before I started, as is typical of a violinist from a Conservatoire I hated rock music and I thought that

the electric guitar only made a horrible noise, sheer disaster! Once, I was at a concert given by the excellent

pianist and composer Rabinovich in the Skryabin museum; when we left the museum we heard the most fantastic sound,

superb!! It was a record being played in the cellars of the museum where a rock group had its studio. I asked who was

playing on the disc and I was told that it was a guitarist called Fripp. I stayed the whole night listening with the

people in the group and decided that I must have a musical experience like this. So I started playing rock music and

life was incredible. The museum officially closed at 5.0 p.m.. During the day I was a Romantic violinist and I

practiced and rehearsed and then I stayed in the studio until dawn every night! We played, we recorded and we

improvised.

Only I played from music, the others in the group said that if they had had to use written music they would not

have been able to play any more, but I, on the other hand, couldn't play without music. In that studio they taught

me what our relationship is with sound, what sound is. As a Romantic violinist I had learnt to play with a uniform

sound. For me sound per se is the highest achievement; and the ultimate in violin sound is that of Heifitz I played

with the group for two years, using an amplified violin and could not bear to listen to classical violins:

no musical authority except in the sphere of jazz and rock existed for me at that time - nothing else. I think

that all classical musicians should have an experience of this sort, all musicians should get to know the music

of their time. They taught me to improvise during concerts in front of an audience. In days gone by the aristocracy

listed to Mozart and Bach and that was the music of their time. In Telemann's days they did not listen to Palestrina,

they listened to the music being composed at that time. It is a good thing that people listen to early music nowadays,

but it is sad that they do not get to know the music of their time. The problem is that it is practically impossible

to play early music and avant-garde music at the same time. They are two different worlds and each requires a different

psychological approach.

in the "Boomerang" rock group

in 1974. Before I started, as is typical of a violinist from a Conservatoire I hated rock music and I thought that

the electric guitar only made a horrible noise, sheer disaster! Once, I was at a concert given by the excellent

pianist and composer Rabinovich in the Skryabin museum; when we left the museum we heard the most fantastic sound,

superb!! It was a record being played in the cellars of the museum where a rock group had its studio. I asked who was

playing on the disc and I was told that it was a guitarist called Fripp. I stayed the whole night listening with the

people in the group and decided that I must have a musical experience like this. So I started playing rock music and

life was incredible. The museum officially closed at 5.0 p.m.. During the day I was a Romantic violinist and I

practiced and rehearsed and then I stayed in the studio until dawn every night! We played, we recorded and we

improvised.

Only I played from music, the others in the group said that if they had had to use written music they would not

have been able to play any more, but I, on the other hand, couldn't play without music. In that studio they taught

me what our relationship is with sound, what sound is. As a Romantic violinist I had learnt to play with a uniform

sound. For me sound per se is the highest achievement; and the ultimate in violin sound is that of Heifitz I played

with the group for two years, using an amplified violin and could not bear to listen to classical violins:

no musical authority except in the sphere of jazz and rock existed for me at that time - nothing else. I think

that all classical musicians should have an experience of this sort, all musicians should get to know the music

of their time. They taught me to improvise during concerts in front of an audience. In days gone by the aristocracy

listed to Mozart and Bach and that was the music of their time. In Telemann's days they did not listen to Palestrina,

they listened to the music being composed at that time. It is a good thing that people listen to early music nowadays,

but it is sad that they do not get to know the music of their time. The problem is that it is practically impossible

to play early music and avant-garde music at the same time. They are two different worlds and each requires a different

psychological approach.

What kind of programs did you play? I have always played in lots of concerts, sometimes I played with the rock group even though it was not very clear from the program what we were going to play: avant-garde, rock, improvisation, people  only had to see who would be

performing and who were the authors of the music. I did this until we were prohibited to. I then went to the Ministry

of Culture and told them that I would give up all my prizes and qualifications, all my concerts, everything, if only

they would officially allow me to continue playing with the rock group. But they wouldn't: rock was western music,

underground, western ideology, rock'n'roll, Pepsi-cola, Coca-cola - it was all American: Evil!

only had to see who would be

performing and who were the authors of the music. I did this until we were prohibited to. I then went to the Ministry

of Culture and told them that I would give up all my prizes and qualifications, all my concerts, everything, if only

they would officially allow me to continue playing with the rock group. But they wouldn't: rock was western music,

underground, western ideology, rock'n'roll, Pepsi-cola, Coca-cola - it was all American: Evil!

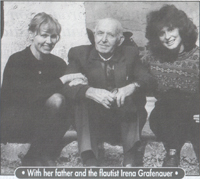

Can you tell us something about your contacts with the contemporary composers at that time, who are now known all over the world? Schnittke for example, you played his Fourth Concerto at the Settembre Musica Festival: it is almost a sonata for violin and piano. Is this one of your favourite pieces? I like some of Schnittke's works, but not all of them. The Concerto Grosso No. 1 is one of his most important works; it is almost pop music. My father, for example, was an officer in the Soviet Army, he liked Mozart and Tchaikovsky, but not Schostakovich: too modern, but he liked Schnittke's music and understood it. It is music that even an officer in the Soviet can understand. Part is a different thing, not everyone understands it even today. All the people in my rock group came to my concerts of baroque music and also loved Part's music. The first version of "Fratres" is for renaissance instruments, for the Hortus Musicus orchestra, and when they played Part you had a mystical sensation, there was a formidable atmosphere. I also played Fratres on original instruments and there is a lot of Part's music in the repertory of my orchestra the Moscow Academy of Early Music. I also love Arvo's "To Sara 90 years"; it is a piece for bells and voice. He wrote it for his wife when she was expecting a baby, and she sang it. The recording you made for ECM with Kremer, of the Tabula Rasa made Part famous in the whole of the world. With "Tabula rasa" many of my colleagues went into crisis. When musicians played it for the first time they were terrified. They didn't know where to start. They experienced the difference between meditative music and, say, Brahms: in Brahms there is a whole forest of sounds, where you can find a bit of everything, in meditative music there are three sounds and you can find all you want in them. If you have got talent you can manage to understand this difference, and consequently to understand Part. With Part there are few sounds but a gigantic human dimension. ItacaInforma |

|

|

World premiere of complete work February 18, 2009 London Royal Festival Hall, United Kingdom Vladimir MARTYNOV, Opera VITA NUOVA More Info The Monk Thogmey's Thirty-Seven Precepts - new disk of Anton Batagov is released More Info The 1st International Festival of Joint Projects "Amplitude" 25th, 28th of September More Info LONG ARMS FEST- 4 (2007) September 27-30, October 6-27 -- FOURTH presentation of the MAIN INTERNATIONAL VANGUARD FORUM OF TWO CAPITALS -- LONG ARMS in Moscow and APOSITION FORUM in St. Petersburg. More Info 10 April, 2007, concert In memory of Nick DMITRIEV Dom Cultural Center more info 13, 14 of November, 2006 Moscow Composers Orchestra on London Jazz Festival More Info LONG ARMS FESTIVAL - 3 September 27 - October 4, Moscow, 2006 DOM Cultural Centre More Info 8, 9, 10 of July 2006 the play "Mozart and Salieri. Requiem" by Vladimir Martynov music. 14, 16, 17 of July the play "Song XXIII. Interment of Patrokl. Games" by Vladimir Martynov music More Info 10th of April, 2006 Nick, we remember you... A film about Nick Dmitriev is now available for download. The film was shown in 2004 on Russian Channel TV Culture DivX (300 mb) download now 23d of November - 2nd of December, 2005 5 performances of "Unorthodox Chants" Project in UK and Belgium More Info 17th-19th of November, 2005 Festival in Tokyo in memory of Nick Dmitriev More Info 1st-10th of October 2005, Long Arms Festival - 2 in memory of Nick Dmitriev see website 1st of July, 2004, 19:00 OPUS POSTH Ensemble performs THE SEVEN LAST WORDS OF OUR SAVIOUR ON THE CROSS by Joseph Haydn Kozitsky lane., house 5 metro Puschkinskaya, Tverskaya, Chekhovskaya information - 299-2262 LONG ARMS new music festival in memory of Nick Dmitriev  from May 15 till 19 IN CONCERT STUDIO M.Nikitskaya str., 24 organized by DEVOTIO MODERNA CENTER and RADIO CULTURE GTRK composers Martynov, Batagov, Karmanov, Aigi, Zagny, Pelecis, Rabinovich, Semzo, Glass, Dresher and others performers Tatiana Grindenko, Galina Muradova, OPUS POSTH ensemble, Anton Batagov, Sergei Zagny, Alexey Aigi, 4.33 ensemble, Tibor Semzo, GORDIAN KNOT ensemble, ALKONOST choir and others book tickets |

|

Intro

Personalities

Institution

Projects

CDs Production

Press

Contacts

Subscription

Links

(C) 2004 Девоцио Модерна, admin@devotiomoderna.ru |

|

|